T.I.A // This Is Africa

For those who are wondering why It looks like I'm doing many different things at once alongside my nutritional coaching career, I’m also a part time anaesthetic nurse at a hospital on the Gold Coast, Australia. I was fortunate enough to have been selected to join a surgical maxillofacial team this year and travel across to the other side of the planet (which seemed to me more like landing on a completely different planet) to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). These are my experiences in words and photos, that just won’t give any justice unless you go there yourself.

I had never been to Africa before. This was always on my bucket list and finally I had the chance to go over and use my skills, so with my OCD I researched and studied this part of the world I was going to, watching numerous documentaries, watching the news and reading up on the violent history which made up what is the DRC. Little did I know that nothing would or could prepare me for what I was about to experience.

On arrival to Rwanda, we met with our personal driver who took us on a 3 hour journey to the Virunga National Park, where we had planned to chill out for 3 days and hike up the volcano to do a trek and find some Mountain Gorillas (you can read and see my photos from this amazing experience here). I couldn't help having my eyes glued to what was going outside my window for that entire drive. I hardly saw any cars, all I saw were people on the rubble filled streets, barefoot and on a mission. Women with babies hanging off their backs and a load on top of their head. Even children carrying their baby siblings wrapped on their back. Men walking with dead goats, or chickens. Boys carrying 100’s of pieces of bamboo or massive 10L water containers on their wooden bikes (known as a chukadoo). People surrounded by an open street fire, cooking some type of animal. Mud houses without windows or front doors. Women washing clothes in a dirty basket and hanging everything on trees and hedges (only to be dusted up again by the streets). Elderly people walking with tree sticks to help them hobble along. People in farming fields shovelling and digging. Buildings under construction with bamboo sticks as scaffold, nothing to secure them into place. Small children aged anywhere between 1 years old and up just walking on their own. And the most confronting of all, UN military soldiers on every corner, with big guns and bullet necklaces wrapped around their necks.

It appeared pretty quickly these people have nothing. I knew I was entering a developing country… but it really hit me what ‘nothing’ actually ‘looked’ like. The only way to explain what it’s like is a different planet far far away from Earth. But it's not, it's right here just a plane ride away. While we’re over here saving for a holiday and materialistic things, there are people over there who don't even know what electricity or what a hot shower feels like. Some of these people had huge smiles and some hung their head down low. Your initial question is what these people weigh, 40kg to 50kg max. You won't see overweight people walking the streets, obviously due to a mixture of malnutrition (or not having the luxury to overindulge in junk food), walking absolutely everywhere and living in a high altitude area. What they do have is luscious greenery everywhere and amazing 360 degree views from being over 2000m above sea level, the view just takes your breath away… literally (I take my hat off to those who train in high altitudes, I struggled just walking about).

Eventually we made our way across the border into the DRC to travel into Goma, where we worked for the next couple of weeks in a small hospital. One of the only hospitals in Eastern Congo. Crossing the border by foot into ‘No Man's Land’ was one of the most chilling experiences. I had to show my invitation into the country (obtained some weeks before jetting off), paid a $300 US visa entry fee (who knows where that even goes), prove all my vaccinations, get my temperature taken, gave some random all our luggage to take over to the other side and hand over my passport. All at the same time as watching hundreds of UN military troops do their thing. I didn't get my passport back for about an hour. Talk about high stress. I had to do that all on the way back into Rwanda coming home. There are no words to explain that feeling of uncertainty in the middle of Central Africa. Luckily I was surrounded by an awesome group of people who had done this trip many times before me.

The word culture shock is definitely what I'll use to open this next paragraph. It was almost like going back in time to the early 1900’s in terms of sexism and woman inequality, racial issues, hierarchy in the workplace, corruption and bureaucracy. I won't go into intricate details because we will be here all day but the things I will mention is this. I quickly figured out women are inferior, in fact so much so they cannot go anywhere, do anything or even get a surgical procedure done without the hand written permission of their husband. Young girls are still being sold with a dowry to other families for organised marriages. Before I realised all of this, a Congolese theatre staff member asked me why my partner gave me permission to go there and why he didn't accompany me, I was confused. I responded back saying I never asked him, I just told him about my plan of going to The Congo. The look of horror was obvious. We then went on into a conversation about culture differences, how women in Australia have equal rights, and we choose our husbands, we earn just as much as males if not more depending on our position, that its perfectly okay for black and white people to be married, men are there with us when we are giving birth and we don't have to experience it alone, men in our country also take on and share the parenting role while some women go back to work, we don't have to pay off government officials or police for anything and we vote for who we want to run our country. We sat in silence for a while, as he took all of that in, and I took in the fact he lived in a country that was completely opposite to mine.

The people I worked with in the hospital were absolutely beautiful. So friendly, welcoming, happy, excited and motivated to learn from our Aussie team. It broke my heart to realise we were doing big 10 hour+ cases and they were doing a ridiculous amount of overtime, without getting paid (long cases are not the norm there, they stick to basic and quick surgeries usually including things like broken bones from road accidents and burns from open fires). The women who work in the hospital all need to leave by 3pm, because they walk hours to get to work and hours to get back home, if they walk the streets after sunset they’re at high risk of getting raped.

We had a super successful trip, operating on patients with large bone tumours, cleft lip/ palate, and other facial deformities. Some who would have died from their airways being occluded if they waited any longer to remove these monstrous and fast growing tumours. You can see some photos below. The thing I kept thinking about is how we never see anything like this back home… facial tumours and so many deformities in children. And its because we’re so lucky to have a health care system that is essentially free, or we have the funds to have health insurance, which would never let us get that far gone. Not only this, but we have the luxury of having a fantastic pre-natal care system where mums to be are well educated on the importance of nutrition, vitamins and other essentials for healthy bubs. The women over there have absolutely no education, no idea and most sadly, are usually alone throughout their journey. Here, we have expensive tests to see if our babies are healthy or have a condition, over there - this is totally non existent. The odds of even coming across an ultrasound machine is next to none. Here, we make tough decisions whether to keep a baby or not according to these test results. Over there, there is no choice, and on top of that, no knowledge about why their children are the way they are and no idea how to look after them.

Despite all the suffering these people endure, they are just so warming and lovely anyway. My girlfriend Anna who came with me went last year also and sponsored a 1 week old baby who had less than a year of life expectancy. Her mum was the definition of poverty and could not afford to keep herself fed and alive let alone her newborn daughter. Her short versioned story goes along the lines of nearly finishing high school about to go to university but being raped and falling pregnant. She had dreams and aspirations of getting herself and her family out of the rut they were in, and then all her plans fell apart. So Anna the little legend decided to sponsor her and the baby last year, to help with food and mums tuition fees. We went to visit them while we were in Goma. We were driven into a tiny shanty town where houses were made of tin and mud bricks and the roads a bumpy rubble mess. We were warmly greeted by mum and the family, Anna nearly being balled over by a huge hug and kiss. They obviously had tidied up the house for us, but if I could find any words to explain a clean mud house… I’ll let you know. We couldn't believe how people were living everyday over there, sleeping on floors, no electricity, no protection, no money… This gorgeous family were so thankful to Anna for all that she had done for them in the last year, with her now 1 year old daughter looking like a healthy normal chubby baby (which is very rare in Africa to see a child as ‘chubby’). They said goodbye to us and gifted Anna with two live chickens, one of the most bizarre and funniest moments we have both ever experienced. To put things into perspective, two chickens cost what this family make in a month. How beautiful and generous is that. Thats what I mean… they are just lovely people. Who would spend a month of their wage here to say thank you to a stranger? I can't think of many.

Now that I’m home, people keep asking me what I struggled with the most, and I don't really know where to start. Maybe the cold shower every night or the electricity working intermittently even in our beautiful and well kept accommodation. I could also talk about the internet working only within a one hour window of the day at dial up speed, or the fact I had to eat potato and rice every day - no vegetables or healthy foods at arms reach. Not having safe tap water (where even most locals don't drink it). There was no time to exercise the entire time, but even if there was there's absolutely no way it would have been safe enough for me to go find somewhere to gym anyway. The streets were a no-no, so I was completely confined to our accom unless working at the hospital. My routine was sleep-eat-work-repeat. I also experienced what it felt like to be a ‘white woman’ in The Congo, constantly being stared at, touched and followed by randoms and having derogatory words thrown at me by locals walking past. Then there was the language barrier… english being their third language at about 60% rate of understanding, it was difficult to get messages across.

I found that the people I worked with never wanted to disappoint us. They would answer ‘yes’ to everything even if the real answer was ‘no’ or ‘I don't know’. Literally, I would say something like ‘ WE ARE HAVING AN EMERGENCY… I NEED THIS INSTRUMENT, WHERE IS IT?’ and I would get a response of ‘Yes’ and just have that person staring blankly back at me smiling. You can only imagine how tiring this got by the last day. There is no sense of urgency in their hospitals, no time management or pre-empt of the future (no planning for emergencies or planning for anything for that matter), no organisation or things placed in ‘a spot’ like your kitchen pantry is laid out or a stock cupboard at your place of work, and now I understand why, why would there be when death is so inevitable. Finding things was like finding a needle in a haystack, going through piles and piles of what we would call rubbish to try find something vital such as a monitor for general anaesthetic. And if that wasn't hard enough to grasp, everything you needed, or needed to do was always behind a locked door. But alas, the man with the key was nowhere too be found (an awesome read is ‘The Man With The Key Is Gone’ by Dr. Ian Clarke, click here to read more about this book). We would be in a total emergency such as the time a woman needed an emergency c-section. They walked her all the way from her bed to the theatre door, in labour and in absolute agony, only to realise they forgot to ask the man with the key for the key!! I asked ‘ where is the man with the key, can we call him’ and I got a blank stare back like I was a crazy white lady… I then found myself walking around the hospital looking for some guy I didn't know with ‘the key’. I lost track of how many times something like this happened. Everything was slow motion, no rush, no urgency… its called ‘Africa Time’ - something I am definitely not used to in our fast paced, doing-a-million-things-at-once environment.

With a statistic of 40% of people in Africa having HIV or AIDS, you can imagine that number being on my mind all day long working with mass amounts of blood and bodily fluids. Like I mentioned earlier, I’m an anaesthetic nurse dealing with people’s airways and helping to maintain them hemodynamically stable day in and day out, but I was lucky enough to have a snapshot and taught the ways and life is a scrub sister, by helping my girlfriend Anna and scrubbing in after she had been on her feet for hours on end for these lengthy operations. Just imagine, no sterilisation of instruments, re-using things we would use one time only, no organisation, no hygiene, no special area for sharps, needles and sutures, squirting arteries and a lot of blood. I wont say any more.

On reflection of my entire experience, I have to say it was truly amazing. And I would totally do it again. For every person who works in the health profession, I highly recommend doing something like this at least once in your life. Even if you're not a health professional, there are so many orphanages and other charities that need your help in third world countries. Its truly an amazing experience and I cant explain how you feel after you've done something like this. Just take my word for it.

What I’ve learnt from doing this is what's important and what isn’t. We get so hung up on trivial things and materialism, fame, judgement, money, fears, beliefs… when you go to a country like the DRC, all of this no longer means anything to you. I’ve realised what it's like to live in a free country, where I can speak my mind and have an opinion, have rights as a female, have a top health care service where specialists in their field are absolutely amazing at what they do, using multi million dollar research and equipment to bring us back to health. I’ve seen what having no money looks like. Money means nothing, how can it be that people with nothing are happier and more carefree than most westerners? Because it does not bring you pure happiness, maybe temporary, but not sustainable happiness. I’m so grateful for having running water and healthy food to eat, a clean beach to walk on every morning and a roof over my head with locks on the doors and windows. I can walk down the street without being attacked but I can also drive a car or catch a train if I need to. I don't have to ask anyone for permission to do anything. And most of all, I have more than I ever need.

I still don't think I will ever be able to fully explain everything, there are just no words to compare life in Africa. I could write for days and days. Its definitely changed my perception on a lot of things. One thing I do keep getting is a lot of praise from people who read all the individual patient stories from my Facebook page. I don't know how to take it, because I feel like I don't deserve any praise. If I could finish off saying anything, it will be this. This is what I do everyday at work, along with millions of other nurses and doctors around the world. The only difference is that I was allowed to publicly talk about everything we did over there on a public forum, and I did it to share awareness of not only what real sickness looks like, but what's going on a few hours plane ride away from you. So this is dedicated to every nurse, doctor and health professional who spend their days saving the lives of strangers… you are on this planet for a reason. Do your thing, and do it well x

An article by The Guardian, published two weeks before my arrival. In it, The DRC dubbed as the rape capital of the world.

The equivalent to the everyday tradies ute and tray to get to work...

Home for two weeks, a theatre made of tin and 40 degrees inside. Electricity working intermittently.

The 'technical department' of the hospital. Built on shipping containers.

People walking to and from their destinations, no cars in sight... except ours.

This man was awake for this... he broke his femur bone in a car accident.

Motorised suction, that only worked when the electricity was on, if it was on.

Our beautiful accommodation in Goma, looking over the vast volcanic lake 'Lake Kivu'.

Another successful surgery on this little bub. You can read the story of little Emmanuel by clicking here.

The 'chukadoo'. An amazing bike made completely out of wood. Young boys will begin to make these in their early teens, collecting wood and other materials over the years. When they finally finish it and can use it effectively, it is said they're ready for marriage.

The Chukadoo up close, getting loaded up.

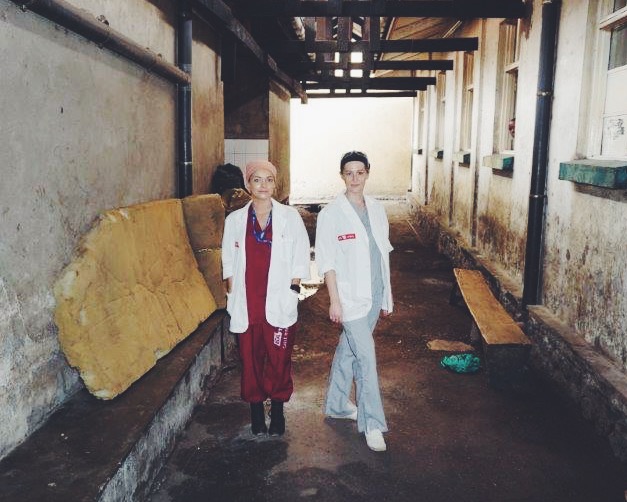

Anna and I standing outside the hospital kitchen.

Ventilators of the anaesthetic machines didnt work. So manual ventilation for the entire procedure was required. No such thing as autopilot here!

Their sterilization unit, where all instruments go to get cleaned...

This mans mandibular tumour was removed, along with 3/4 of his jaw. A rib was taken from him to use as a graft and replace what was his jaw. The surgery was a total success!

Anna and I on our way to work.

Exiting The DRC, on our way home after passing through No Mans Land.